Karim Rashid does not require an introduction; he is by far the most prolific designer of his generation. Distant from tradition – he loves to play with colors, creating designs that build a connection with and elevate the human experience. He has designed everything from trashcan to hotel, and metro to furniture – his poetic and fluid designs know no bounds; they motivate, inspire, question, and challenge our minds to look beyond the obvious and appreciate innovation.

We can talk endlessly about the brilliance of this design superstar, but we will reserve that for another story – for now, head straight to our conversation with Karim Rashid to learn in-depth about his favorites, his suggestions to young designers, and how he believes design would change in post coronavirus era.

Homecrux (HC): First of all, many congratulations on winning the 2020 American Prize for Design. How has your journey been?

Karim Rashid (KR): Thank you so much! I have flashbacks of when I was in university designing projects, staying up all night, so passionate, reading and obsessed with designers such as George Nelson (who started the GOOD DESIGN AWARDS in 1950), Charles Eames, Achille Castilioni, Sottsass, and so many others and feeling deep inside that I had the talent, focus, and the perseverance to become one day successful as they were. Then I ended up studying with Ettore Sottsass and Gaetano Pesce and working in Milano with Rodolfo Bonetto. I also saw hundreds of lectures from Buckminster Fuller to George Nelson to Mario Bellini to Alessandro Mendini. Afterward, I returned to Canada and worked 6 years as an industrial designer for Kuypers Adamson Norton (they were the most important firm in Canada, and there I designed many ‘below the line’ projects such as seats for trains, machinery for the military, power tools for Black and Decker, hospital beds and even a mammographer, to the point where I felt far too creative for this kind of design. It is essential but it discouraged me from my desire to create poetic consumer products. I started teaching in Toronto and eventually segued into full-time academia and taught at Rhode Island School of Design and Pratt institute (I moved to NYC I 1993), and University of Arts, Philadelphia. But I could not stay away from design and decided to continue designing as I taught. Eventually, I stopped teaching and focused on my design practice, and now 27 years later feel immensely proud of what I have accomplished.

HC: Describe your love affair with design? How do you think your designs are different?

KR: My designs are a manifestation of my soul, like a composer creating music. I am trying to create Good Design. Good design is when the human experience is elevated, simplified, engaged, and inspired. Good design has a human connection with us. Design is about creating the physical utopia of our everyday life.

HC: Form, futurism, and pallet of colors dominate your designs. Why so much emphasis on these elements and how do you manage to strike the right balance in tandem?

KR: Creativity is not enough in design. Design must answer to all the issues of use, behavior, aesthetics, manufacturing processes, material’s ecological issues, marketing, dissemination, etc. The more in tune we are with the commercial world, the more relevant our work is.

HC: Your pursuit of beauty and originality for design started in the mid-’90s. As a young designer, what were your biggest roadblocks when design was insular and dull?

KR: The biggest roadblock was access to clients. In 1993, I found myself in New York City penniless and started drawing objects romanticizing about the beautiful world I always wanted to shape. When I started my office, after approaching about 100 companies from Lazy boy to Gillette, I only got one client. That was 27 years ago!

HC: Garbo was a sexy and adventurous twist to a mundane household item. How did it shape your future as an industrial designer?

KR: Garbo was a case of rationalism meets sensualism which has been an ethos of my career. At that time, the ubiquitous plastic wastebasket on the market was a rectangular black can with absolutely no character and there was little alternative. I immediately thought of a sensual, yet functional object and it taught me that design must work. It can be artistic, conceptual, but must always function perfectly.

HC: From water bottle to furniture to hotels and restaurants, there’s an array of projects that display your design prowess. Is there a particular genre you love working in?

KR: I was brought up in a household where my father designed everything, from my mother’s clothes to the furniture in the home. I think I decided when I ran my own practice that I would stay as pluralist as possible, kind of like a Warhol factory, or an Eames factory, and to try to do cross-discipline kinds of things. I am designing a line of fashion, jewelry, eyeglasses, headphones, water bottles, furniture, interiors, architecture, painting, and ambient music. The common thread of all these disciplines is industry. They are all part of the world of Industrial Design. I am an advocate of pluralism and cannot thrive under specialization. I think the rest of the design world (fashion, product, interior) is beginning to think broadly as well.

But right now I love designing buildings. I sketch and render a lot of conceptual work but there is much interest in making it a reality!

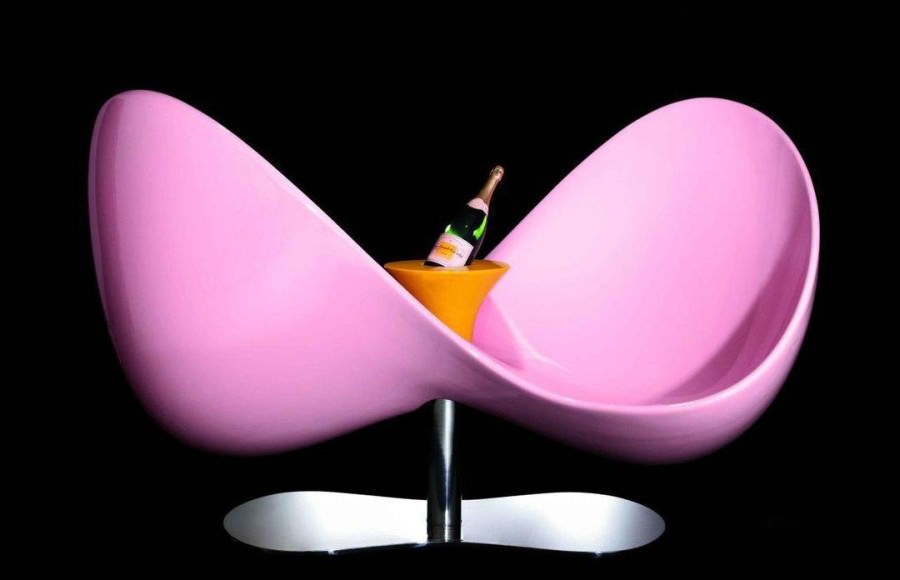

HC: Our favorite is Veuve Clicquot loveseat, if you have to choose one, which one is yours?

KR: As with most creative people, it is difficult to have a favorite since my mind and passion is always into my latest projects. This past Fall I opened my first full resort, Temptation, Cancun. I’ve designed hotels before but this is a fascinating subject as it is an adults-only, topless-optional resort. I’ve designed the building, public spaces, rooms, 9 restaurants, and a giant sensual pool. But I am more excited for the next Temptation, Punta Cana, which will be designed by me from the ground up.

But if I must choose products then I am proud of the Garbo can for Umbra that I designed in 1994 since it is 20 years old and still so successful, faucets I designed for Cisal in 2007, and ovens for Gorenje as they were my first foray into appliances. My other favorite design is the Kaj watch for Alessi. I have all 12 colors so I change them every day. They are so light, so comfortable, so simple, and inexpensive, which is really my mantra. I must say that I enjoy from micro to macro, anything and everything that creates a better human experience.

HC: You are known as the Prince of Plastic. Why?

KR: I loved plastic since I was a child. Plastic wasn’t just another material to me –but it was the lively, energetic material of all materials. I would argue that plastic is now part of our nature. Polymers have democratized our consumer landscape, and afford us the most beautiful, highest quality inexpensive goods that we use every day. So for me, to design with plastic affords me to create a super comfortable lightweight stacking plastic chair that can last 30 years and only costs $30. Polymers can be sculptural, poetic, ergonomic, fluid, sensual, warm, high performing, and very accessible materials.

Now there are organic plastics. I am obsessed with working with responsible plastics that are biodegradable, recycled, or even derived from other sources like corn, sugar, bark, and acai instead of oil. The Garbo can is now made of corn and biodegradable and the Snap chair by Feek is made of 100% recycled polystyrene and is 97% air. This year I debuted the Siamese Chair from A Lot Of is made of plastic injection with Ipê Roxo. Ipê Roxo is one of the most exported woods from Brazil. Its bark is very rich in medicinal nutrients, the removal of the bark that completely regenerates in 2 years, happens especially in the Amazonian region. 40% is discarded for being excessively moist. The percentage that is usually eliminated is now used to develop the liquid wood.

HC: Considering the current situation (Coronavirus pandemic), how do you see the role of a designer changing? Can design help fix this and how?

KR: It has been inspiring to see the design community rushing to make change – redesign and re-purpose manufacturing capabilities to make ventilators, high-end cosmetic companies are making hand-sanitizers, clothing for nurses and doctors, home-designers using their 3D printers to create mask parts for first-responders and even new modifications to make doors hands-free. Despite our distance, we will be a more collaborative and kinder society. What inspired me is to see a quieter city, a cleaner city, a cleaner earth with less pollution, and many reconsidering the perpetual burden of Capitalism. Capitalism is a non-stop machine that has created an artificial desire for perpetual growth, but we could have an economy that is stable, gives, jobs, gives meaning, without growth. What’s wrong with a small business that stays small? Why do conglomerates have to show shareholders every year a 5% or more growth? Let’s slow down and make less, consume less, take care of each other and our planet.

HC: Is this situation affecting your life and business? What are your future plans?

KR: The first thing I must say is many people have lost their jobs (40 million people in the USA alone have applied for unemployment insurance) and having trouble surviving so there is no reason for anyone who still has a job or is finically stable to complain or be negative about this experience. Staying home is for many a moment to slow down and reconsider one’s existence, and to reflect and reconsider ones meaning. I find in this time with few obligations and a completely open schedule a personal need to create constantly. I have to draw every day for about 2 hours. So, every day, I sit at my small humble home office surround by color and visual energy, I pull out a bunch of paper and invent projects. Even though I’m down to about eight projects in my office, where usually at this point, I’d have 50 or 60. I’ve sketched out my designs and all of a sudden, I’ve got nothing else to do. And for me, it’s very, very unusual. I’m so used to being absurdly busy. Start creating by thinking about the situation in the world around us and what’s going on and see if it inspires ideas. After approx. 2 months I am now quite disciplined with my day. I wake early and stretch. Then make a strong oat milk Latte, a small breakfast (usually cashew yogurt and berries) and I listen to local news. Then I put on a different playlist every day (I have about 30,000 tracks divided into many playlists). Then I start sketching. I work out 90 minutes a day that includes a 45 min run on a treadmill in my living room. I have eggs at lunch, every day a different way of cooking them, and I then do social media and answer many friends, fans, etc. In the evening I always have an organic salad with some grilled protein and do the 7 pm clapping ritual to hear all the positive new Yorkers energy. I read than watch an interesting arthouse film every night.

I look forward to realizing many projects that are on hold. And I typically travel more than 50% of the year. But to be honest I don’t miss flying. In fact, I think we all will do less travel for business and realize our digital tools can save the planet by consuming less energy. I never understood why it was so important to have physical meetings that would require someone to go halfway around the earth for a few hours. So, let’s put less planes in the sky, manufacture locally, farm locally, and slow the world down.

HC: What’s been your most challenging project? One creation that is a true reflection of Karim Rashid?

KR: My most challenging project was probably my design for Naples Metro. It is my longest project to date! I started in 2004 and it wasn’t completed until 2011. But I am very proud of the finished product. They selected various famous architects to design each station. The stations in Naples are referred to as ‘Art Stations’. Gae Aulenti’s station has work by Michelangelo Pistoletto and Joseph Kosuth. Some stations have art from Sol Lewitt to Sandro Chia. Alessandro Mendini likes my sensibility, which was really flattering considering I aspired to his vision when I was in university and always saw him as a mentor. Since the stations were under the auspices of art, this afforded me to rather than design a station that is somewhat conservative and ‘accent’ it with art, I just did the whole station as my digital art. So I sunk the art budget into the interior walls and spaces instead of selecting art. I will always love the impact and challenge that was the Naples Metro. It is the epitome of democratic design.

HC: Design is in you and your skin (tattoos). Care to share the story behind the ink?

KR: I developed the language of my icons over a period of 35 years. It started when I was designing power tools for Black and Decker, USA in the mid-eighties. Black & Decker refused to give designers credit for work so I created a symbol which I embedded into the plastic molding. It was a way of marking my work, of denoting my creative input. Then I continued to create more symbols, each with a certain meaning. I can write prose with them. The symbols were non-lingual therefore not biased and anyone and everyone could interpret them as they saw fit. The beauty of abstraction will always be self-interpretation and higher spiritual meaning. Words are precise and forms are vague. I continued to work and develop these symbols over these last 20 years and they started to become an integrated part of my life, even to the point of tattooing myself twice a year with them, each different symbol done in a different city to continue my quest and belief for a global oneness.

I use them in my patterns and forms and even have them tattooed all over my body. Each symbol has a meaning, and I now associate those symbols with the cities in which I got them tattooed. Once a year I try and get a new tattoo in a city in which I am working. I have 23 tattoos in 23 years one from each city around the world, except 2 from NYC. My first tattoo was done in Toronto 23 years ago. It is my symbol for globalove because Toronto is a melting pot (even more so than NYC) and hence the globe is there and symbiotically living and loving together. I get one around my birthday every year. I have Cairo with my birth ikon, I was just in Tel-Aviv to review the opening of Poli house Hotel and made a lecture at the Holon museum and I designed an ikon called ‘strength’ since it is such a small country yet so strong spreading art and culture globally. I combined the ikons for “non-stop” and ‘designocracy” while I was in Istanbul to speak about how turkey produces high quality in expensive products globally and a city that is non-stop from prayer to energy and determination. I got my undulating data-driven wireframe while in NYC because the globe is totally data-driven and New York is the epicenter of globalism, I have my signature I did in London because I am half British and so on and so on. They’re like luggage or passport stamps!

HC: Other than you who’s your favorite designer(s)?

KR: Here is an edited list: Luigi Colani, Ettore Sottsass, Joe Columbo, Philip Starck, George Nelson, Charles Eames, Isamo Noguchi, Ross Lovegrove, Bruno Munari, Carlo Mollino, Gaetano Pesce, Joe Columbo, Victor Papanek, David Carson, Frederick Keisler, Shiro Kuramata, Buckminster Fuller, Zaha Hadid, Oscar Niemeyer, Toyo Ito, contemporary artists such as Dalek, Dutchman, David Bowie, Gober, Charles Ray, Jeff Koons, Peter Hailey, Andy Warhol, Gerold Miller, the list goes on…

HC: Finally, your favorite color and material? Why?

KR: I love pink and techno colors- colors that have a vibrancy and energy of our digital world. There are really millions of colors so it is ridiculous in this life to have a single favorite of anything- favorite song, favorite book. The beauty of this farrago in life is the broad diversity and choice of everything. I love color and I am not afraid of it – I use it in a painterly way as a way of driving emotion through our physical object’s our spaces, to expression motivate, to inspire, and question, to challenge, and touch or evanescent public memory.

HC: Any suggestions for budding designers?

KR: For young designers, I always give the advice: Be smart, be patient, learn to learn, learn to be really practical but imbue poetics, aesthetics, and new paradigms of our changing product landscape. You must find new languages, new semantics, new aesthetics, experiment with new material, and behavioral approaches. Also always remember obvious HUMAN issues in the product like Emotion, ease of use, technological advances, product methods, humor, and meaning and a positive energetic and proud spirit in the product.

Follow Homecrux on Google News!