Amid modern-day designers, there are a few who can rest their hands on the shield inscribed with Veni; vidi; vici. However, I believe if anyone has earned the bragging right to wear the Latin phrase as a crest, it’s the veteran designer Marc Sadler.

The Milan-based industrial designer has won the reputed ADI Compasso d’Oro award numerous times and has had an illustrious career spanning over half a century. Almost 50 years back, Sadler started his journey as a student learning the tricks of industrial aesthetics and now motivates the younger generation to create beautiful, functional, sustainable designs.

I had the pleasure to have a conversation with Marc Sadler who discusses his journey and touches on the aspects of 3D modeling prominent in the design industry today. In an exclusive chat, the doyen of the design world also opens up on his struggles with injuries and how much he loathes being called the ‘design machine.’

Homecrux (HC): Tell us about your journey as a young designer, and how have you dealt with success and failure in a career spanning over five decades.

Marc Sadler (MS): My pathway starts from far away at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (ENSAD) in Paris. During my third year (around 1968) the first “industrial aesthetics” course of study opened (there was no mention of design yet), and I joined with enthusiasm.

After graduation, together with a group of friends, I opened the Design Center Premier, one of the first associated groups of professionals to sell services related to industrial aesthetics (design, graphics, interiors, installations). At that time, perhaps because we were helped by the fact to be in Paris, we mostly worked with companies in the fashion world, including Pierre Cardin and Yves Saint Laurent.

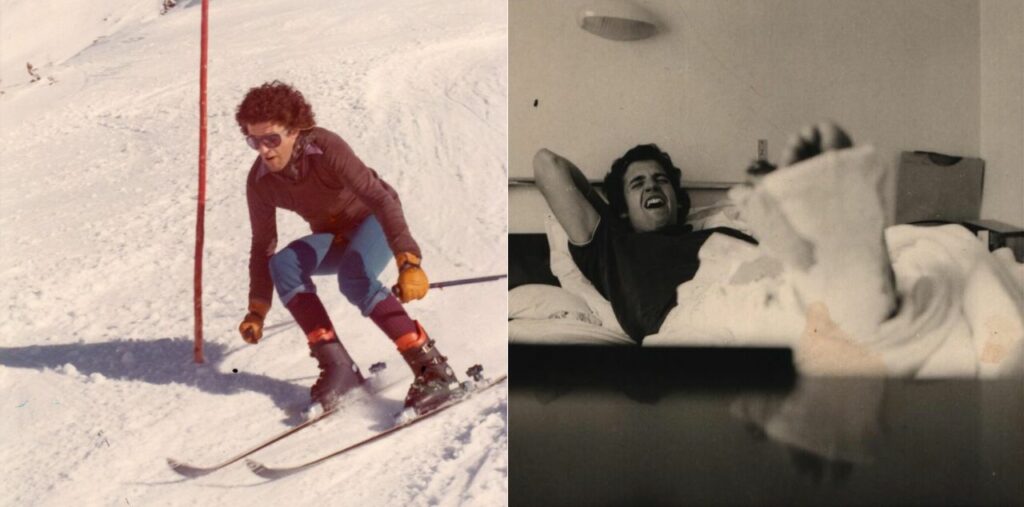

A ski accident in the Alps took place in 1970 in Les Deux Alpes, a true Paradise for skiers. The accident occurred during a very foggy day, I was so young and reckless not to understand that it was not the right thing to do. Briefly, I fell into a crevasse that I couldn’t see, and I was quite lucky to break my ankle bones only!

The shoes were leather boots, i.e. the standard ones available at that time. During my (long) recovery (I had surgery three times, definitely unlucky about that!) I had enough time to think that such accidents could have had less painful consequences if ankles were secured by a rigid boot. So, I started to arrange a sort of plastic boot, by testing it in a domestic oven, and its outcome was exhibited in the students’ area at Ispo in Germany, the most important fair for sports. At Ispo I had the chance to get in touch with a famous Italian producer of leather boots who fell in love with my funny idea … and that’s the way the story started!

For the record, that prototype did never work, but we kept on with the idea of the thermoplastic boot, and many other projects were developed in collaboration by consequence.

HC: You are both, a designer and an architect. How do you strike a balance between the two? What is your winning mantra?

MS: I do not have the licensing to operate in Italy as an architect, which means that I cannot sign the projects and have civil liability over them. As one of the first graduates in industrial design in France (at that time called aesthetique industrielle i.e. industrial aesthetic) I have focused my career around industrial design, acting all over the aspects of product design.

HC: You have collaborated with names like Foscarini, Teckell, Olev, and countless more. Which one would you say is your favored design/collaboration and why?

MS: Collaborations involve a personal relationship with the entrepreneur who looked for my service, while designs are the result of such relationships. When the good matching of the two happens it means “the squaring of the circle.” I always like to tell the story of the collaboration with Foscarini which led to the birth of the Mite lamp.

At that time (2000) I lived in Venice and I used to meet the two partners of Foscarini in the early morning in the Vaporetto (they used to go to Marcon, the inland village where Foscarini is based) while going to visit my customers. It’s been an unusual situation that gave us the courage to open our cooperation on a brave premise: get over the Foscarini glass tradition to explore new horizons.

The idea was to use Kevlar and carbon fiber in association with the fishing rod technology, both Foscarini’s partners accepted the challenge with enthusiasm! That was the genesis of our first lamps made together: the Mite family. We have been working together for a long time with trust built up over the years, and there is still strong mutual credibility to think of new projects together.

HC: You’ve touched every facet of design we can think of – be it lighting, furniture, accessories or sporting gear – what’s your preferred genre?

MS: None in particular, meaning that every field interests me. I am open to new experiences and keep on believing that there is no branch that has reached the point where there’s nothing more to say or invent. That said, I do like the lighting design because I believe that light has some magic in itself, and its dressing design is fascinating.

HC: Young designers we speak to use 3D CAD and other software to render their ideas today. From days of drafting papers to state-of-the-art software, how have you adapted? How easy/difficult has it been for you as a veteran craftsman?

MS: As a “differently young” designer, I grew up in a moment when 3D modeling didn’t exist, everything was made by hand. Today, after years of overwhelming virtual models, I definitely see the return of the real, physical model. This is a very useful exercise for the designer to make the first tests on a project and moreover it results much more appealing and convincing for the client. However, I live in the present, and I cannot deny that design software has a key role. Curiosity is a peculiar part of me and I don’t stop in front of the generational rejection (and the consequent handicap) toward technology.

HC: You are often referred to as the ‘design machine?’ What is brewing in your design factory at the moment?

MS: I wouldn’t endorse such an unpleasant definition, at the same time I have a considerable number of projects in the pipeline: some routine projects, some more difficult, some with well-known companies, some others with less famous but perhaps more dynamic ones, however, I don’t like talking about projects until they are in the public knowledge.

HC: You are an avid traveler who’s worked in different regions of the world. How has this experience helped shape your design philosophy?

MS: I was born in Austria by chance, my parents were French and I have French citizenship too. I lived in Austria for four years after my birth, then the family moved to Baden-Baden and finally to France. Soon after graduation, I moved to Italy to work closely with Italian facilities in the ski-boot district, then the US together with recurring round trips to Europe and the Far East. Such a stateless way of living influenced my design style, which is expressed by the fact of not having it too marked, almost the antithesis of design branding.

I quote the incipit of a recent article in a magazine that I fully agree with: “For an author, stylistic recognition can be positive but at the same time it can be the origin of his ruin, or at least of his audience’s weariness”. The reference was not to design, but the concept is transferable: an overly defined style, which may have been the recipe for great success, can become slavery, become synonymous with déjà vu, in the best case when the “sign” is changed may no longer be recognized. And for arrogant designers, recognition is an element that is difficult to give up.

When I was still living in France, I designed a metal wire lamp for Chabrière, a Marseille-based editor of artistic products. It was one of my first works and looked like a minimalist sculpture, but when the light was switched on, it became “something else,” with a language all of its own. With a dual approach, I gradually learned to use it as a design opportunity.

HC: At times, creative ideas don’t materialize as intended. In such situations how do you deal with critical feedback? Any word of wisdom for budding designers on handling pressure better?

MS: Creative ideas rarely come at the right moment, when it happens it’s a lottery win. My suggestion for the young generations is “study, try, always put yourself into question”, learn the history of design, the great designers of the past or the present and go deep into the reason for their talent, learn the different industrial techniques, be tirelessly curious.

There are no limits to the creation of beautiful, functional, sustainable designs. Lots of common products that we use every day are obsolete under these points of view, that’s why good designers of the future must be able to give new answers, without forgetting what has been done up to now.

However, in industrial design, unlike in art, performers can never forget that the product they are conceiving must be sold by the industry and generate profit margins, otherwise, it means a dangerous failure, given the significant investments behind the projects that are often spent. The reasons for a defeat are several, both from designers and entrepreneurs: a “wrong design,” i.e. a project that is misinterpreted by the designer, or the lack of quality in the product, i.e. the entrepreneur’s failure in production, or the lack of promotion, or confused distribution, etc. When there is a valuable dialogue between the designer and the company right from the start, all these risks reduce.

We would like to thank Marc for taking the time to answer our questions.

Follow Homecrux on Google News!